Gita (Victim of Ajmer Rape Case 1992) Age, Family, Biography & More

Gita is one of the girls who was the victim of the Ajmer Rape Case, which happened in 1992. This case is considered one of the most shocking incidents in India. It happened in Ajmer city, Rajasthan, where many young girls, most of them Hindus, were sexually assaulted and blackmailed.

Ajmer Rape Case (1992)

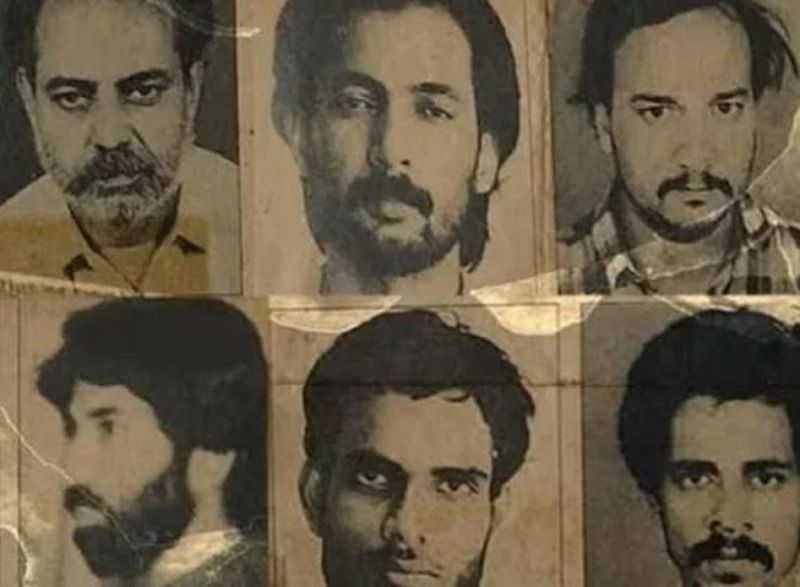

The 1992 Ajmer serial gang rape and blackmailing case is indeed regarded as one of the most heinous and horrific crimes in India. The severity and brutality of the assaults, along with the subsequent exploitation and blackmail faced by the victims, have left a lasting impact. The case brought to light the vulnerabilities and challenges faced by rape survivors, especially when powerful individuals are involved. It also exposed the influence of certain groups in hindering justice and protecting the culprits. The scandal came to light when a local newspaper called Navajyoti published some private pictures and reported that school students were being blackmailed by local gangs. The police began to investigate the case, but they faced pressure from politicians because the main accused, Farooq Chishti (Chisty), was connected to powerful groups in the area. He was the president of the Ajmer Indian Youth Congress and a Khadim of Ajmer Sharif Dargah. Despite this pressure, the court managed to charge 18 people involved in the serial offences. However, four out of the eight who were convicted and given life sentences were later acquitted in 2001. Later, on 20 August 2024, Nafees Chishti, along with his partners Naseem alias Tarzan, Salim Chishti, Iqbal Bhati, Sohail Ghani and Syed Zameer Hussain, was sentenced to lifetime imprisonment by a Pocso court. This case has been compared to the Rotherham child sexual exploitation scandal, which occurred in a town called Rotherham in Northern England from the late 1980s until the 2010s. Both cases involved heinous crimes against young people, leading to public outrage and a demand for justice.

Gita- One of the Victims

Gita, a victim in this case, was a student in class 12 at Savitri Girls Government Primary School in Ajmer, Rajasthan. She had aspirations to join the Congress party and also desired a gas connection for her home, which was relatively uncommon at that time. Her classmate Ajay took advantage of her situation and introduced her to Farooq Chishtee (Chisty/Chisti), the President of Ajmer Youth Congress, without revealing his and his brother Nafis Chishti‘s intentions. Gradually, Farooq gained Gita’s trust, and she didn’t suspect anything when he and Nafis intercepted her in their van while she was on her way to school and offered her a lift. Trusting them, she accepted their offer, but instead of taking her to school as promised, they took her to a farmhouse. There, she was subjected to brutal rape by Farooq and Nafis, who also took objectionable pictures of her to blackmail her. They forced her to bring other girls to their farmhouse on Foy Sagar Road, threatening to leak her private photos if she refused to comply.

Testimony of Gita

In a 2003 Supreme Court ruling, Gita provided a detailed account of the sexual assault she experienced and the subsequent blackmail by the Chishty duo and their associates. According to her testimony, Gita had multiple encounters with Nafis and Farooq, often accompanied by her classmate Ajay. They would approach her in their Maruti van while she walked towards the bus stand, assuring her that they would help her secure a position in the Congress party. Their associate, Sayed Anwar Chishty, later gave her forms to fill out and requested a passport-sized photograph from her. During her testimony, Gita revealed that she believed the detour to the farmhouse was for discussions related to her potential entry into Congress. However, as soon as she was alone with Nafis, he forcibly assaulted her and threatened her life if she didn’t comply with his demands. Several days later, Nafis confronted her again, reiterating the severe consequences she would face if she disclosed the assault to anyone. Under coercion, Gita was forced to introduce the men to other girls, portraying them as her brothers and building trust with the intention of convincing these girls to attend parties at the farmhouse or Farooq’s bungalow on Foy Sagar Road.

Subsequently, many of these women became victims of sexual assault by one or multiple men. The perpetrators would often capture photographs of the assaults and use them to blackmail the victims. Dalbeer Singh, a source involved in the case, expressed concern about how the media sensationalized the situation by focusing on the fact that some of the victims were daughters of IAS-IPS officers. He emphasized that while one victim was the daughter of a Rajasthan civil service officer and another was the daughter of an agriculture officer, it was crucial not to overlook the severity and gravity of the crimes committed. During Gita’s testimony, she revealed how the criminals manipulated and coerced her into finding other girls for their sexual exploitation. Falling into their trap, she befriended a girl named Krishnabala, who also became a victim of Farooq. In the 1990s, while Gita was studying at Savitri Government Girls Senior Secondary School in Ajmer, Rajasthan, she became close friends with Krishnabala, who lived in a rented house in Civil Lines, Ajmer. Unaware of the manipulative intentions of Farooq and Nafis, Gita was coerced into bringing more women to their group under the threat of having her nude photos exposed publicly. During Gita’s testimony, she recounted a distressing incident from the early stages of the gang-rape incidents. Gita and Krishnabala sought help from a police constable to retrieve the photos.

The constable introduced them to an officer from the special branch of the Ajmer police. However, after involving the police, they started receiving threatening phone calls, causing them to fear the consequences of their actions. The constable even took them to the Dargah area to retrieve the photos, but they were unsuccessful in their attempt. The Chishty family wielded religious influence, and officials would often approach them for negotiations and favours, making it challenging for others to deny their requests. The women’s worst fears materialized when some employees at the photo lab where the assault images were printed began circulating the pictures, further perpetuating the abuse. This led to the case gaining public attention, drawing greater scrutiny to the situation. Later, journalist Santosh Gupta shared that a reel developer named Purshottam had bragged about the sexually explicit photos when he caught his neighbour, Devendra Jain, looking at a pornographic magazine. This incident added to the gravity of the case and its impact on the victims. Purshottam had sneered,

This is nothing. I’ll show you the real stuff.”

Devendra’s alarming discovery prompted him to make copies of the pictures and send them to the Dainik Navajyoti newspaper and the local Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) group. The VHP workers then handed the photos over to the police, leading to an investigation. On 21 April 1992, journalist Gupta wrote his initial report about the sexual exploitation of Dainik Navajyoti, but it didn’t receive much response. However, when the paper published a second report on 15 May 1992, which included blurred pictures of the unclothed survivors, it immediately sparked public outrage. The situation escalated on 18 May 1992, as the entire city of Ajmer shut down due to public anger over the case. In her testimony in 2005, Krishnabala recalled that the survivor used to talk about having five Muslim brothers who seemed generous. However, things took a dark turn when she received a seemingly normal party invitation. Upon arriving at a poultry farm in Hatundi, on the outskirts of Ajmer, Nafis and another prominent member of the gang, Ishrat Ali, were already present. Krishnabala stated that she was raped by Ali on that day. Later, Ishrat dropped her home at 5 pm, warning her. He said,

If you tell anyone about this, I will defame you. You must come whenever summoned, or else I can do the same to your sister.”

After Krishnabala returned home and washed her blood-soaked clothes, she fell victim to a relentless cycle of blackmail. She was repeatedly called and threatened with exposure. On one occasion, she was summoned to Farooq’s bungalow on Foy Sagar Road in Ajmer, where she was subjected to rape by four men: Nafis Chishti, Anwar Chishti, Salim Chishti, and Ishrat Ali. Shockingly, this pattern continued for the next eight months, during which she endured 25 instances of gang rape. [1]The Print

Role of Print Media in the Case

In April 1992, Deenbandhu Chaudhary, the editor of Navajyoti, a local newspaper in Ajmer, published a report that brought to light a disturbing system of deceit and exploitation. Chaudhary revealed that despite being aware of the scandal for about a year before the story broke, local law enforcement authorities deliberately stalled the investigation. He further disclosed that local politicians attempted to hinder legal action by arguing that the accusers belonged to influential “khadim” (caretaker) families of the dargah, and taking legal measures could lead to inter-communal tension. He said,

It was difficult to decide whether to publish the photographs or not.”

Chaudhary and his team decided to move forward with the story because they believed it was the only way to compel the local administration to take action. They saw the publication of the report as a crucial step in shedding light on the issue and urging authorities to address the situation seriously. He said,

Finally, we decided to go ahead because it was the only way to shake the administration and police out of their slumber.”

Following the publication of Chaudhary’s report, the news of the incident reverberated through the town, causing widespread shock and outrage among the citizens. In response, angry protesters organized public demonstrations during a three-day bandh to demand justice and accountability. Under immense public pressure, the BJP Government was compelled to order an investigation into the matter. However, state BJP Secretary Onkar Singh Lakhotia admitted that the delay in taking action was a result of the accused individuals’ political influence and their connections to influential families associated with the dargah,

The action has come too late.”

Following the initial report, a series of subsequent stories emerged, shedding light on the widespread blackmail and exploitation that had been occurring. As a result of the investigation, eight of the accused individuals were charged, leading to the arrest of a total of 18 men. The town of Ajmer was fraught with tension for several days as the situation became apparent. However, as former deputy inspector general of police in Ajmer, retired DGP Omendra Bhardwaj, pointed out, many more victims were likely deterred from coming forward due to the social status and influence of the accused individuals. Some of the victims, who were young and vulnerable, had already taken their own lives. The subsequent events revealed a tale of political influence and administrative incompetence. Many of the victims who were supposed to testify later turned hostile, and only a few were willing to come forward. This situation was indicative of the challenges faced in seeking justice in such cases.

Victims Who Suffered in the Case

Several of the victims in the case were daughters of IAS officers or IPS officers, belonging to affluent Hindu families. Most of these victims suffered in silence, facing harassment and threats even after the rape, without receiving adequate support from social groups or family members. Police investigations indicate that around six victims were believed to have tragically taken their own lives due to the trauma they endured. The threats and intimidation extended to the point where Ajmer Mahila Samooh withdrew from advocating for the victims, presumably fearing reprisals. During that period, local tabloids and papers sensationalized the case, exacerbating the town’s distress. These media outlets allegedly further blackmailed the victims by holding explicit photographs of the girls and demanding money from their families to keep them hidden. The entire situation was distressing, leaving the conscience of the town deeply troubled.

In Popular Media

In 2007, Anuradha Marwah published a book titled ‘Dirty Picture,’ which is based on the events of the Ajmer Rape Case in 1992.

In 2023, a Hindi film titled ‘Ajmer 92’ was released, inspired by the Ajmer rape case. The character of Geeta Singh in the film was loosely based on the real-life survivor Gita, and the role was portrayed by the Indian actress Sumit Singh.

References/Sources: