K. Parasaran Age, Wife, Children, Family, Biography & More

Quick Info→

Age: 96 Years

Wife: Saroja Parasaran

Hometown: Chennai

| Bio/Wiki | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Kesava Iyengar Parasaran |

| Other name | Parasaran Kesava Iyengar |

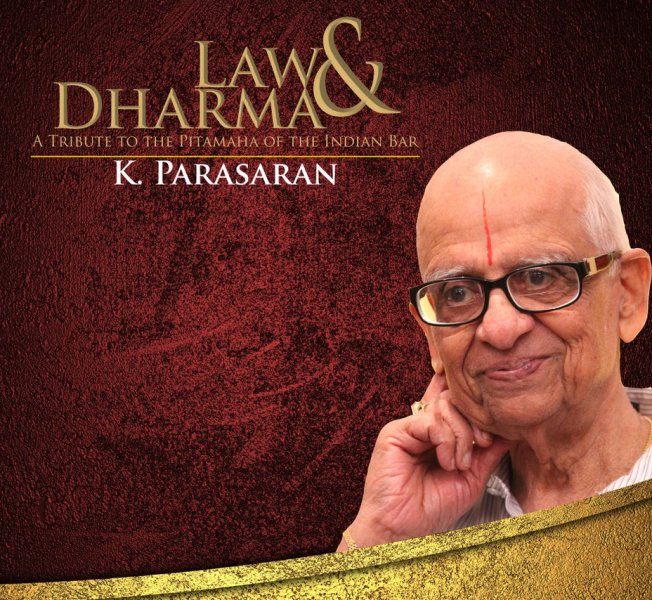

| Names earned | Pitamaha of the India Bar Note: Sanjay Kishan Kaul, a former Supreme Court judge, gave this name to Parasaran as a recognition of his legal contributions while respecting his religious beliefs. |

| Profession | Advocate |

| Famous for | Representing Hindu parties in the Sabarimala case and Ram Janmabhoomi case |

| Physical Stats & More | |

| Height (approx.) | in centimeters- 168 cm in meters- 1.68 m in feet & inches- 5’ 6” |

| Eye Colour | Dark Brown |

| Hair Colour | Grey (semi-bald) |

| Career | |

| Notable Cases | I. C. Golaknath and Ors. vs State of Punjab and Anrs. (1967) The Supreme Court, in its ruling, said that Parliament lacked the authority to restrict any Fundamental Rights mentioned in the Constitution of India. Maru Ram Vs Union of India (1981) The Supreme Court determined in this case that the President and the Governor of a state lack the authority to unilaterally pardon a prisoner. Instead, the power to grant a pardon is confined to the recommendation of the Council of Ministers in their respective governments. R. K. Garg Vs Union of India (1981) This case was filed by R. K. Garg in the Supreme Court, challenging the implementation of the 1981 Special Bearer Bonds (Immunities and Exceptions) Act. In his plea, he said that the Union government did injustice to the honest citizens by shielding those with black money, purchasing the bonds, from the IT Department's inquiry regarding the source of the money from which they bought the bonds. S. P. Gupta Vs Union of India (1981) The apex court held in this case that the recommendations of the Chief Justice of India (CJI) for the appointment of judges in the court cannot be considered obligatory. S. P. Mittal Vs Union of India (1983) This case dealt with the definition of "religious denomination" as outlined in the Indian Constitution concerning the concept of religious freedom. Sheonandan Paswan Vs State of Bihar (1983) This case examined the authority of a public prosecutor to step back from a case. The Supreme Court held that the public prosecutor has the constitutional right to withdraw from a court case involving an individual, provided that the court grants consent. Hoechst Pharmaceuticals Vs State of Bihar (1983) Hoechst Pharmaceuticals took legal action against the Bihar government regarding the enforcement of the Bihar Finance Act of 1981, which imposed taxes on pharmaceutical companies in the state. The Supreme Court ruled in favour of the Act, affirming its constitutional validity. Union of India Vs Bombay Tyre International Ltd. (1984) In this case, the apex court established the criteria for subtracting post-manufacturing costs when calculating the assessable value for tax deduction according to the Central Excise Act. LIC Vs Escorts Ltd. (1986) The Supreme Court examined the importance of Article 14 of the Indian Constitution in scenarios where a government-owned entity possesses shares in a corporation. Indian Express Newspapers Vs Union of India (1985) The Indian Express initiated legal action in the Supreme Court, seeking a ruling on the taxation of newspapers. The petitioner contended that taxing newspapers was in violation of Freedom of Expression. The Supreme Court ruled that while taxes couldn't be imposed on the exercise of freedom of expression, they could be applied to various sectors, including the newspaper industry. Sampath Kumar Vs Union of India (1987) In this case, the petitioner raised concerns about the constitutionality of judgments delivered by Administrative Tribunals formed under Article 323A. The Court, however, held the constitutional validity of both, Article 323A, and various clauses in the Administrative Tribunals Act. Kehar Singh Vs Union of India (1989) In its decision, the Supreme Court stated that, under Article 72, the President of India has the authority to re-evaluate the evidence in a criminal case and arrive at a sentencing decision which is different from that of the court. Indra Sawhney Vs Union of India (1992) Indra Sawhney, the petitioner, contended that the 27% reservation allocated to the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) for government services should not extend to the "creamy layer;" those earning above Rs. 1 lakh annually. The petitioner also argued that the reservations for OBCs in promotions within government positions should not be implemented. Unni Krishnan Vs State of A. P. (1993) Unni Krishnan, the petitioner, raised concerns about the Andhra Pradesh government's responsibilities in giving education. The apex court held that the Article 45 only guarantees the Right To Education to those below the age of 14. The court also said that the inclusion of the right to receive education for those over the age of 14 shall depend on the development of the respective state's economy as well as its infrastructure. R. C. Poudyal Vs Union of India (1994) In the apex court, Poudyal, while citing the breach of the secular principles of the Indian constitution, contested the allocation of one seat for the Sanghal minority (Buddhist Lamaic Religious Monasteries) and the twelve seats reserved for individuals of Bhutia-Lepcha origin in the Sikkim Legislative Assembly. The court determined that the state legislature, in accordance with the power granted under Article 371F of the constitution, had the authority to reserve seats. S. R. Bommai Vs Union of India (1994) The petitioner, Bommai, filed this case concerning the imposition of the President's Rule (under Article 356) leading to the abrupt dismissal of state governments. The Supreme Court emphasized that the Central government should not invoke President's Rule for political motives but only in genuine emergencies. Additionally, the court laid down principles to limit the application of Article 356. T. N. Seshan Vs Union of India (1995) Seshan, who served as the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) at that time, filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court to contest the Central government's approval of Article 342(2), which resulted in the selection of two extra Election Commissioners (ECs). The court, however, ruled in favour of the Union government. J. Jayalalitha Vs M. Chenna Reddy (1998) Jayalalitha, the ex-Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, challenged the authority of the Governor of Tamil Nadu to initiate legal actions against a Chief Minister. The Supreme Court gave its decision in Jayalalitha's favour, stating that a state's Governor does not have the authority to sanction the initiation of a criminal case against a Chief Minister. P. A. Inamdar Vs State of Maharashtra (2005) It focused on the imposition of quotas in unaided professional institutions and the administration of admission exams for such colleges under Article 30 of the Indian constitution. The Supreme Court determined that the Maharashtra state government did not possess the jurisdiction to dictate admission and administrative policies for educational institutions established by minorities. M. Nagaraj Vs Union of India (2006) Nagaraj, the petitioner, challenged the Union government's power to modify the constitution for expanding reservation in job promotions to SCs/STs in public services. The Supreme Court, in its verdict, emphasized that the government must adhere to the 50% reservation limit, exclude the Creamy Layer (similar to OBCs), and demonstrate the actual backwardness of the specified caste or tribe. Ashoka Kumar Thakur Vs Union of India (2008) Ashoka Kumar Thakur contested the 2006 Union government's decision to allocate a 27 percent reservation for OBC students in government colleges, as per the Mandal Commission's (1992) recommendations. The Supreme Court upheld the government's decision but stated that individuals falling within the Creamy Layer, earning more than Rs. 2,50,000 annually, should not benefit from the reservation. The Sabarimala Case K. Parasaran defended the Nair Service Society in the Supreme Court as they aimed to restrict the access of menstruating women to the Sabarimala temple, citing the celibacy of Lord Ayyappan, the temple's deity. In his argument, Parasaran referred to verses from the Sundarakanda of the Ramayana and spoke of "Naishtika Brahmacharya," highlighting Lord Ayyappa's celibate character. In his arguments, Parasaran said, "If a person asks ‘can I smoke when I pray’, he will get a slap. But if he asks, “can I pray as I smoke, he will be appreciated. So, the right question will bring the right answer, a wrong question will bring a wrong answer." The five-member Supreme Court bench, led by Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi and including Justices Rohinton Nariman, A. M. Khanwilkar, D. Y. Chandrachud, and Indu Malhotra, rejected the Parasaran's arguments and, in the end, allowed women to enter. Ayodhya Land Dispute Case The case initially began in the Allahabad High Court and later reached the Supreme Court. It was regarding the land allocation for the construction of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh. K. Parasaran, acting as the legal representative for the Hindu parties, advocated for the infant deity Ram Lalla Viraajman. In 2019, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court rendered the decision. The court assigned the contested Ram Mandir site to the Hindu parties and directed the Government of India to establish a trust for overseeing the temple's construction. The court also instructed the government to allocate land to the Waqf Board for the construction of a mosque.  |

| Awards, Honours | • Honourary Degree in Doctor of Law from the Annamalai University, Tamil Nadu (1989) • The Great Son of the Soil Award by the All India Conference of Intellectuals (2002) • Sadhana Award for Excellence in Law and Public Affairs from the Samudhaaya Foundation (2003) • The Padma Bhushan from the Government of India (2003) • Rashtriya Samman from the Central Board of Direct Taxes, Chennai Region • Centenarian Lifetime Achievement Award from the Centenarian Trust (2005) • National Law Day Award from the Indian Council of Jurists (International Lawyers Network) • Most Eminent Senior Citizen Award from Vice President M. Venkaiah Naidu (2019) • The Padma Vibhushan from the Government of India (2011) • Award of Law Legend by the Revenue Bar Association (RBA) (2012) • SILF-MILAT Professor (Justice) A.B. Rohatgi Jurist Award from the Society of Indian Law Firms and Menon Institute of Legal Advisory Training (2015) • An award during the Constitution Day celebrations from the CJI (2016) • An award for outstanding contribution to the development of the legal profession in India as well as for his deep involvement and conscientious encouragement in the promotion and maintenance of the highest standard at the Bar (2016) • For the Sake of Honour Award from the Rotary Club (2017) • Most Eminent Senior Citizen Award by Age-Care India (2019)  • Sree Narayana Guru Award for Social Work by Swarajya Marg (2020) • Sivananda Eminent Citizen Award from the Government of Tamil Nadu for his contribution to the field of law (2020)  • Dr. Hedgewar Pragya Samman Award in Chennai for his contribution to the field of law (2022)  |

| Personal Life | |

| Date of Birth | 9 October 1927 (Sunday) |

| Age (as of 2023) | 96 Years |

| Birthplace | Srirangam, Madras State, British India (now Tamil Nadu, India) |

| Zodiac sign | Libra |

| Nationality | British Indian (1927-1947) Indian (1947-present) |

| Hometown | Chennai, Tamil Nadu |

| School | The Hindu Higher Secondary School (HHSS), Chennai |

| College/University | • Presidency College, Chennai • Madras Law College (now known as Dr. Ambedkar Government Law College), Chennai |

| Educational Qualification(s) | • BA (Economics) at the Presidency College • LLB at the Madras Law College Note: He received Shri Justice C.V. Kumaraswami Sastri Sanskrit Medal and the Justice Shri V. Bhashyam Iyengar Gold Medal while doing law. |

| Religion | Hinduism Note: He is a follower of Lord Parthasarathy. |

| Caste | Pancha-Dravida Brahmin |

| Address | House number 8, Eighth Street, Dr. Radhakrishnan Road, Mylapore, Chennai – 600004, Tamil Nadu, India |

| Relationships & More | |

| Marital Status | Widower |

| Marriage Date | 11 July 1949 |

| Family | |

| Wife/Spouse | Saroja Parasaran (deceased on 6 July 2010; philanthropist) Note: She did social activism with various NGOs. |

| Children | Son(s)- 3 • Mohan Parasaran (advocate, served as the Solicitor General of India during the UPA-II regime)  • Balaji Parasaran (lawyer) • Satish Parasaran (senior advocate, Tamil Nadu Bar Council member)  Daughter(s)- 2 • Rangam Balaji (literary scholar, lyricist)  • Vasupradha |

| Parents | Father- R. Kesava Aiyangar (deceased at the age 99; vedic scholar, practiced law at the Madras High Court and Supreme Court) Mother- Ranganayaki |

Some Lesser Known Facts About K. Parasaran

- K. Parasaran is an Indian advocate, well known for representing religious cases in the court of law. He has gained prominence for representing Hindu parties in famous cases such as the Sabarimala temple entry ban case as well as the Ayodhya land dispute case. Parasaran has served in several prominent legal positions within the government, including as the Advocate General of Tamil Nadu, the Solicitor General of India, and the Attorney General of India.

- According to K. Parasaran, he had memorized the verses from the Ramayana by the time he entered the seventh grade.

- He took up a job at Madras University, Chennai, after earning his bachelor of arts degree. However, he later resigned from the job to earn a law degree and pursue a career as an advocate.

- After his LLB, he sat for the Bar Council of India exams. He was awarded the Justice Shri K.S. Krishnaswamy Iyengar Medal for passing the exams with flying colours.

- He began his legal practice at the Madras High Court in 1950.

- In 1958, he began his career as a lawyer in the Supreme Court of India. There, he represented his clients in cases related to the Hindu religion.

- He co-established the Revenue Bar Association (RBA) in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, in 1963.

- K. Parasaran was made the Madras High Court’s Senior Standing Counsel by the Indian government in 1971.

- He took over the office of the Advocate General of Tamil Nadu on 17 June 1976 during the emergency. He remained in the post until he resigned from the post in 1978.

- While serving as the Solicitor General of India, K. Parasaran stated in an interview that he informed the Union government led by Indira Gandhi that he would resign from his post if they compelled him to represent them in the court for demolishing The Indian Express building. He further said that he refused to represent the Indian government in the case because the government acted against his advice of not proceeding with the destruction of the building as it was not proven to be illegal. He said,

I advised the government to not act on the show-cause notice issued to demolish the Indian Express building as it was legally untenable. When the Indira Gandhi government ignored my opinion, I refused to defend the government in court and offered to resign if I was forced to appear.”

- He served as the president of the Indian Society of Criminology from 1984 to 1985.

- In 1984, the Bar Association of India selected him as its president; he remained in the post till 1987.

- K. Parasaran, in his role as the Attorney General of India (AGI), headed the Indian delegation to New York. Their objective was to present a report on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights before the United Nations Human Rights Commission (UNHRC).

- He acted as the Indian government’s representative in the legal proceedings against Union Carbide on behalf of the victims of the 1984 Bhopal Gas Tragedy.

- In 1986, he became a permanent member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, Netherlands.

- While Atal Bihari Vajpayee was the Prime Minister, Parasaran served as a member of the National Commission for Review of Working of the Constitution.

- In his capacity as a legal professional, he has actively participated in multiple interstate water dispute cases. Examples include the Cauvery River water dispute between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, the Mullai Periyar Dam safety disagreement between Tamil Nadu and Kerala, and the Krishna River water dispute involving Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Maharashtra.

- Popular South Indian actor Kamal Haasan is the first cousin of Saroja Parasaran, K. Parasaran’s deceased wife.

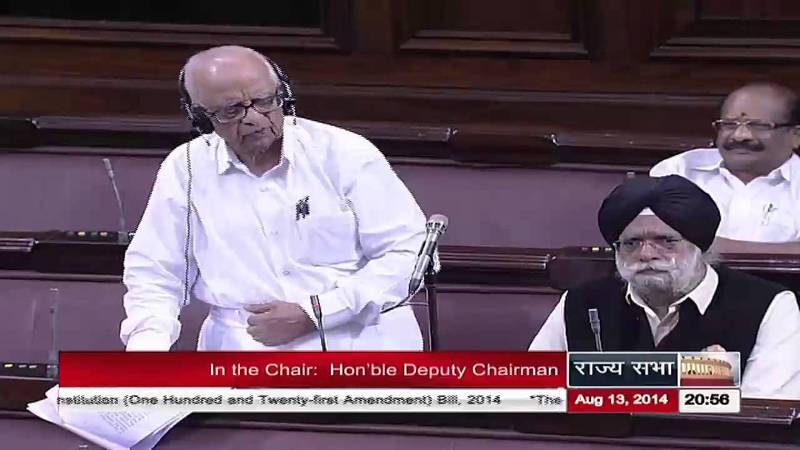

- He entered the Rajya Sabha as its member in June 2012 on the nomination of the President of India. He served as a parliamentarian till 2018.

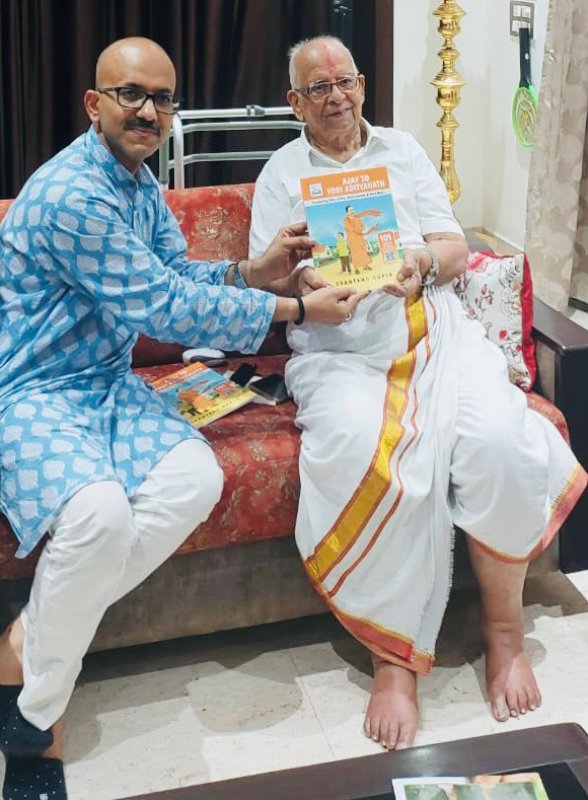

- In 2016, three students from SASTRA Deemed University authored a book titled “Law & Dharma: A Tribute to the Pitamaha of the Indian Bar,” focusing on the life of K. Parasaran.

- Due to his age, K. Parasaran received an offer from Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi during the Sabrimala case proceedings to sit while presenting arguments instead of standing. Despite the offer, he chose to continue arguing while standing. While thanking the judges, he said,

It’s okay. Your Lordships are too kind. The tradition of the Bar has been to stand and argue, and I am concerned about the tradition.”

- In 2019, the Indian government appointed him as the head of the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Teerth Kshetra trust. Later, Mahant Nritya Gopal Das took over his position. The trust is responsible for overseeing the construction of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. According to reports, the trust was initially registered at Parasaran’s home address.

- The ex-Chief Justice of the Orissa High Court, Justice C. Nagappan, served in the Madras High Court as a junior advocate under the apprentice of K. Parasaran.